In the first part of The Lady Civil War Reenactor, I gave an introduction about what should be expected at most reenactments for women, why people choose to participate in reenactments, and a list of vocabulary commonly spoken by people in the reenactment community. In the second part of The Lady Civil War Reenactor, I talked about building the impression (persona) that you use that reenactments and what should be avoided. I also put up a short questionnaire designed to help you build your impression. In the third part of The Lady Civil War Reenactor, I got into more of the specifics in each type of impression that a female reenactor can do, broken down into basic economic and social structure in both the Union and the Confederacy.

Today we’re going to get into the more fun part of reenacting for women – fashion. This blog is going to outline what you will need to get started as a civilian female reenactor and then what things you can add on to your impression as you become more experienced in the reenactment community. I sew most of my own things but what I cannot make myself, I usually get from Abraham’s Lady, which is a sutler shop in Gettysburg, but they also set up shop at different reenactments. There are a great many sutlers out there for men and women, some better than others, but I really encourage the process of researching and making your own things as much as you can because that’s what most people in the 1860s did – they made their own things for the most part.

Dressing the Lady Civil War Reenactor

Getting dressed in 1860s clothing is a process that definitely has steps. The items below are listed in order of how they go on for me. All of these items are necessary to create a well-done impression of any lady in the 1860s. The undergarments were basically the same for all classes but the differences were in the quality of materials.

Budget tips. Outfitting yourself from scratch can be quite costly. A few tips are that you should look for fellow reenactors (veterans, not new people) in a similar size as you and see if you can buy used items from them. Learning to sew is going to save you a lot of money too because seamstresses are going to charge you for hours of labor. I can make my own dresses for around $20-$50 as opposed to a seamstress charging me anywhere from $150-$400 for a single dress. If you have to fudge your impression anywhere to save money, do it where people can’t see the inaccuracy. Reproduction period boots can be quite expensive, so you can buy similar looking modern boots for less than half the price. Corded petticoats are cheaper than hoops too.

If you’re going to be in the reenacting community regularly, however, you need to build your impression as accurate to the period as possible. People will turn a blind eye to farby things like modern boots under your dress if you’re in your first year, but your first year should show strides toward accuracy as well. Save your money the first year and begin replacing farby things with period correct things. Ask advice from reenactors who have been doing it for years and years.

Stockings – Just about every woman in the 1860s wore stockings unless she was simply too poor to afford them. The most important thing I can tell you about stockings is they were not made of nylon. Do not buy nylon. I will say that again. Do not buy nylon. Nylon was not invented until the 20th century. Stockings in the 1860s were made of silk or cotton for the most part. If you’re wondering whether you should choose silk or cotton, that depends on the financial status of your impression. For women could not afford silk, so they would have worn cotton. Women of some standing could afford silk and would do so more often than not. Everyday stockings were usually black and sometimes they were striped. Women who could afford embroidery sometimes chose to have their stockings embroidered or they did it themselves but it was more common for them to be black or striped for everyday use. Formal stockings used for nighttime balls or other formal occasions were white.

Stockings – Just about every woman in the 1860s wore stockings unless she was simply too poor to afford them. The most important thing I can tell you about stockings is they were not made of nylon. Do not buy nylon. I will say that again. Do not buy nylon. Nylon was not invented until the 20th century. Stockings in the 1860s were made of silk or cotton for the most part. If you’re wondering whether you should choose silk or cotton, that depends on the financial status of your impression. For women could not afford silk, so they would have worn cotton. Women of some standing could afford silk and would do so more often than not. Everyday stockings were usually black and sometimes they were striped. Women who could afford embroidery sometimes chose to have their stockings embroidered or they did it themselves but it was more common for them to be black or striped for everyday use. Formal stockings used for nighttime balls or other formal occasions were white.

Chemise – A chemise was the basic undergarment that served as a buffer between the sweat, body oils, dirt, etc., on the woman’s body and her corset and dress. It looked like a shapeless white nightgown with with capped or short sleeves, a scooped neckline, and it cut to about mid-calf on the legs. Virtually all undergarments were made of white cotton or sometimes linen, although I see far more cotton than anything else. It would have been thin cotton for undergarments as well. Sometimes these undergarments could be embellished with lace but in the 1860s, there was virtually no color because the undergarments were washed far more than dresses. Laundry in those days was brutal on fabric, so color would have bled everywhere and faded. It was easier to wash white things and not show the abuse the fabric took in the laundering process.

Chemise – A chemise was the basic undergarment that served as a buffer between the sweat, body oils, dirt, etc., on the woman’s body and her corset and dress. It looked like a shapeless white nightgown with with capped or short sleeves, a scooped neckline, and it cut to about mid-calf on the legs. Virtually all undergarments were made of white cotton or sometimes linen, although I see far more cotton than anything else. It would have been thin cotton for undergarments as well. Sometimes these undergarments could be embellished with lace but in the 1860s, there was virtually no color because the undergarments were washed far more than dresses. Laundry in those days was brutal on fabric, so color would have bled everywhere and faded. It was easier to wash white things and not show the abuse the fabric took in the laundering process.

Drawers or Pantalettes – This was what we would probably think of as underwear, although women in the 1860s did not wear underwear the way we do. Drawers were secured around the waist with a drawstring and they fit around the legs like baggy pants but they were crotchless. The reason for that was the difficulty in using the facilities for a woman with such a big billowing dress. She would not remove everything to use the facilities. She would lift her dress and fit over the privy. If the drawers were crotchless, then she wouldn’t have to fuss with trying to get undressed each time. Again, drawers would have been made of thin white cotton in most cases and the only embellishment would probably have been a little bit of lace around the hem of the legs. Female reenactors are divided on the issue of whether to wear open crotched drawers or close crotched drawers because many seem to feel exposed without some semblance of modern panties. It’s really a matter of personal preference as to whether your drawers are open or closed. If you’re looking for the most authenticity, however, you will want to stay true to the crotchless pantalettes.

Drawers or Pantalettes – This was what we would probably think of as underwear, although women in the 1860s did not wear underwear the way we do. Drawers were secured around the waist with a drawstring and they fit around the legs like baggy pants but they were crotchless. The reason for that was the difficulty in using the facilities for a woman with such a big billowing dress. She would not remove everything to use the facilities. She would lift her dress and fit over the privy. If the drawers were crotchless, then she wouldn’t have to fuss with trying to get undressed each time. Again, drawers would have been made of thin white cotton in most cases and the only embellishment would probably have been a little bit of lace around the hem of the legs. Female reenactors are divided on the issue of whether to wear open crotched drawers or close crotched drawers because many seem to feel exposed without some semblance of modern panties. It’s really a matter of personal preference as to whether your drawers are open or closed. If you’re looking for the most authenticity, however, you will want to stay true to the crotchless pantalettes.

Shoes – You want to put shoes on at this stage before you put on the foundational garments like the corset and hoops because once those things are put on, you won’t be able to bend over enough to comfortably put on your shoes. Ladies shoes in the 1860s were either boots or slippers. Truly accurate boots were worn during the day and they were fastened with buttons along the side, not laces up the middle as many, many sutlers like to sell. You have to be really careful when shopping for 19th century shoes because an untrained eye will mean that you end up with Edwardian looking boots because they are prettier. Slippers were worn to formal occasions and usually resembled what we would know as ballet slippers today. They were delicate and soft-soled – not at all meant to be worn for daily use. Depending on your desired level of accuracy, you can spend a lot of money on reproduction boots or you can slightly cheat by wearing modern boots of a similar shape and color. The reason why it’s only marginally okay to cheat in this case is because people are not very likely to see your feet under the dress unless you lift up your dress too much.

Shoes – You want to put shoes on at this stage before you put on the foundational garments like the corset and hoops because once those things are put on, you won’t be able to bend over enough to comfortably put on your shoes. Ladies shoes in the 1860s were either boots or slippers. Truly accurate boots were worn during the day and they were fastened with buttons along the side, not laces up the middle as many, many sutlers like to sell. You have to be really careful when shopping for 19th century shoes because an untrained eye will mean that you end up with Edwardian looking boots because they are prettier. Slippers were worn to formal occasions and usually resembled what we would know as ballet slippers today. They were delicate and soft-soled – not at all meant to be worn for daily use. Depending on your desired level of accuracy, you can spend a lot of money on reproduction boots or you can slightly cheat by wearing modern boots of a similar shape and color. The reason why it’s only marginally okay to cheat in this case is because people are not very likely to see your feet under the dress unless you lift up your dress too much.

Corset – A corset, along with hoops, are the most important structural foundation pieces that a woman would have worn in order to achieve the 1860s silhouette. The majority of women wore corsets on a daily basis. There are reenactors who don’t wear corsets but they are not really achieving the most accurate look of the time. I cannot stress how important it is to invest in a good corset as early as you can. It is the most expensive piece of your wardrobe but if you invest early, it will last you several years. For the beginning, you can get one off the rack, but if you are going to be a regular on the reenactor circuit, I strongly urge you to invest in a custom-made corset. For custom-made corsets made in the 1860s style, I highly recommend Originals By Kay. And for the love of God, do not buy your Civil War reenacting corsets at Victoria’s Secret or Frederick’s Of Hollywood or any other modern corset maker because they are not the same silhouette and they are not constructed in the same way.

Corset – A corset, along with hoops, are the most important structural foundation pieces that a woman would have worn in order to achieve the 1860s silhouette. The majority of women wore corsets on a daily basis. There are reenactors who don’t wear corsets but they are not really achieving the most accurate look of the time. I cannot stress how important it is to invest in a good corset as early as you can. It is the most expensive piece of your wardrobe but if you invest early, it will last you several years. For the beginning, you can get one off the rack, but if you are going to be a regular on the reenactor circuit, I strongly urge you to invest in a custom-made corset. For custom-made corsets made in the 1860s style, I highly recommend Originals By Kay. And for the love of God, do not buy your Civil War reenacting corsets at Victoria’s Secret or Frederick’s Of Hollywood or any other modern corset maker because they are not the same silhouette and they are not constructed in the same way.

Corset Cover – This is part of the layers of undergarments that were worn in the 1860s but for some reason have gone out of fashion among reenactors. I don’t know very many reenactors who actually use corset covers unless they are rather hardcore in accuracy. The course the cover looks like a short version of a chemise, almost, and its purpose was to protect the corset from dirt and body oils because it was rather difficult to wash such an undergarment. Sometimes they buttoned up the front like the bodice of a dress and sometimes they look like an 1860s version of a modern tank top. I’ve seen a lot of variation. I don’t think there was really much of a standard as to what it should look like as long as it did its job. This particular garment seems to be optional in the reenacting community. If you are looking to be as accurate as possible, then you want to be looking into a corset cover.

Corset Cover – This is part of the layers of undergarments that were worn in the 1860s but for some reason have gone out of fashion among reenactors. I don’t know very many reenactors who actually use corset covers unless they are rather hardcore in accuracy. The course the cover looks like a short version of a chemise, almost, and its purpose was to protect the corset from dirt and body oils because it was rather difficult to wash such an undergarment. Sometimes they buttoned up the front like the bodice of a dress and sometimes they look like an 1860s version of a modern tank top. I’ve seen a lot of variation. I don’t think there was really much of a standard as to what it should look like as long as it did its job. This particular garment seems to be optional in the reenacting community. If you are looking to be as accurate as possible, then you want to be looking into a corset cover.

Petticoats – There were a couple of layers of petticoats. Prior to the invention of the crinoline (hoops), many layers of petticoats were used to achieve the bell shaped skirt. After the invention of the crinoline in the mid-1850s, the number of petticoats dropped to two or three. The under petticoat, sometimes called the modesty petticoat, was worn over the chemise and drawers, and under the hoops. Its purpose was not only modesty but warmth in the winter. Another petticoat was worn over the hoops and sometimes a second petticoat was worn on top of that if the lady desired a smoother skirt. Petticoats worn over the hoops were intended to conceal the harsh lines of the hoops under the dress. Like all undergarments of the time, petticoats were also made of thin white cotton for the most part, although during the winter, many women chose to wear quilted petticoats for warmth. There could be lace embellishments around the hem but I have never seen color embellishments on 1860s undergarments.

Petticoats – There were a couple of layers of petticoats. Prior to the invention of the crinoline (hoops), many layers of petticoats were used to achieve the bell shaped skirt. After the invention of the crinoline in the mid-1850s, the number of petticoats dropped to two or three. The under petticoat, sometimes called the modesty petticoat, was worn over the chemise and drawers, and under the hoops. Its purpose was not only modesty but warmth in the winter. Another petticoat was worn over the hoops and sometimes a second petticoat was worn on top of that if the lady desired a smoother skirt. Petticoats worn over the hoops were intended to conceal the harsh lines of the hoops under the dress. Like all undergarments of the time, petticoats were also made of thin white cotton for the most part, although during the winter, many women chose to wear quilted petticoats for warmth. There could be lace embellishments around the hem but I have never seen color embellishments on 1860s undergarments.

Hoops or Cage Crinoline – This is not as simple as going to your local bridal shop and picking up a crinoline because that would be completely inaccurate. Hoops of the 1860s were a different shape, size and construction. In fact, you’re going to have an extremely difficult time finding hoops accurate to the 1860s even among Civil War reenactors. The correct shape was elliptical, meaning it was not perfectly round. Most of the hoop shape was behind the woman, creating the effect of having a train on her dress even though she didn’t unless it was a formal occasion. The other myth is that hoops were gigantic and impossible to manage. Most of the hoops I’ve seen from the 1860s measured between 90 inches and 105 inches circumference with formal ballgowns widened by flounces on petticoats over the hoops. How wide should your hoops be? There is a formula I’ve seen on another website. First you measure your waist. For example, my waist is 27 inches at the moment. I would take 90 X 27 which equals 2430. Now divide 2430 by 26 and that comes to 93.5. So the appropriate size hoops for my waist would be 93.5 inches in circumference. The closest standard size sold in most sutlers would be 90 inches.

Hoops or Cage Crinoline – This is not as simple as going to your local bridal shop and picking up a crinoline because that would be completely inaccurate. Hoops of the 1860s were a different shape, size and construction. In fact, you’re going to have an extremely difficult time finding hoops accurate to the 1860s even among Civil War reenactors. The correct shape was elliptical, meaning it was not perfectly round. Most of the hoop shape was behind the woman, creating the effect of having a train on her dress even though she didn’t unless it was a formal occasion. The other myth is that hoops were gigantic and impossible to manage. Most of the hoops I’ve seen from the 1860s measured between 90 inches and 105 inches circumference with formal ballgowns widened by flounces on petticoats over the hoops. How wide should your hoops be? There is a formula I’ve seen on another website. First you measure your waist. For example, my waist is 27 inches at the moment. I would take 90 X 27 which equals 2430. Now divide 2430 by 26 and that comes to 93.5. So the appropriate size hoops for my waist would be 93.5 inches in circumference. The closest standard size sold in most sutlers would be 90 inches.

Corded Petticoat – This is an alternative to full-on hoop skirts. Women who were doing a lot of work around the house or in army camps did not usually wear hoops because they were a fire hazard and it was difficult to do a lot of housework dressed in such cumbersome fashion. In other words, women who did not have servants to do the housework would probably be seen in corded petticoats doing chores at home instead of hoop skirts. However, if anybody was coming to visit, they would probably put on their hoops and dress for callers. The vast majority of women owned at least one set of hoops but it’s not accurate to spend your day in camp working over a fire wearing such things because it would have been dangerous. You would have known better if you lived at that time. If your impression is based on being a laundress or cook in the camp, then you would wear corded petticoats as opposed to hoops. The cording made the petticoats a little stiffer to give the dress at least some shape that was the desired silhouette in the period without being too hazardous. I’ve worn the corded petticoat between a normal under petticoat and a normal over petticoat, giving my dress a good shape without having to force hoops into a wheelchair.

Corded Petticoat – This is an alternative to full-on hoop skirts. Women who were doing a lot of work around the house or in army camps did not usually wear hoops because they were a fire hazard and it was difficult to do a lot of housework dressed in such cumbersome fashion. In other words, women who did not have servants to do the housework would probably be seen in corded petticoats doing chores at home instead of hoop skirts. However, if anybody was coming to visit, they would probably put on their hoops and dress for callers. The vast majority of women owned at least one set of hoops but it’s not accurate to spend your day in camp working over a fire wearing such things because it would have been dangerous. You would have known better if you lived at that time. If your impression is based on being a laundress or cook in the camp, then you would wear corded petticoats as opposed to hoops. The cording made the petticoats a little stiffer to give the dress at least some shape that was the desired silhouette in the period without being too hazardous. I’ve worn the corded petticoat between a normal under petticoat and a normal over petticoat, giving my dress a good shape without having to force hoops into a wheelchair.

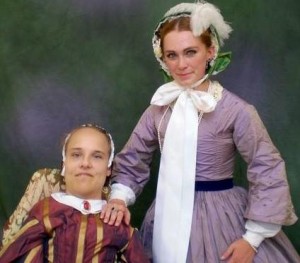

Dress – Finally, finally, finally! After all of the preparation of your 1860s silhouette structural foundation, you’re ready to put on your dress. There is so much variety in dresses that I’ll have to go over them in their own blog. Most dresses that I’ve seen were two pieces: the bodice and the skirt. It was easier to put on the pieces separately than fuss with such a huge single piece. More complicated dresses, such as ballgowns that laced up the back, were usually put on with assistance from someone else. A lot of dresses buttoned up the front or were fastened with hooks and eyes. Women were just as expressive with their fashion in the 1860s as we are today. It was just totally different styles than what we are familiar with, so we tend to think that 1860s women were the same things and weren’t that concerned or somehow incapable of fashion tastes. Even though the basic shape of the 1860s silhouette was the same from woman to woman, how she decorated her dresses and how they were cut, along with the fabric, the patterns and the embellishments all determined a woman’s sense of style. We’ll get into that in the next blog. You will have to develop your own sense of 1860s style.

Dress – Finally, finally, finally! After all of the preparation of your 1860s silhouette structural foundation, you’re ready to put on your dress. There is so much variety in dresses that I’ll have to go over them in their own blog. Most dresses that I’ve seen were two pieces: the bodice and the skirt. It was easier to put on the pieces separately than fuss with such a huge single piece. More complicated dresses, such as ballgowns that laced up the back, were usually put on with assistance from someone else. A lot of dresses buttoned up the front or were fastened with hooks and eyes. Women were just as expressive with their fashion in the 1860s as we are today. It was just totally different styles than what we are familiar with, so we tend to think that 1860s women were the same things and weren’t that concerned or somehow incapable of fashion tastes. Even though the basic shape of the 1860s silhouette was the same from woman to woman, how she decorated her dresses and how they were cut, along with the fabric, the patterns and the embellishments all determined a woman’s sense of style. We’ll get into that in the next blog. You will have to develop your own sense of 1860s style.

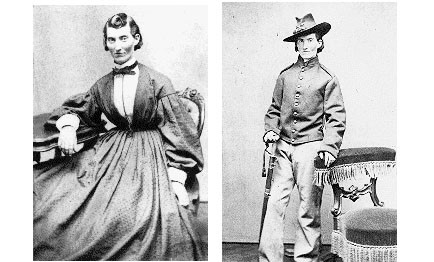

Outerwear – This is a rather important thing that tends to get overlooked by modern women participating in reenactments. A woman in the 1860s never left the house without covering her head with a bonnet or hat and a pair of gloves, along with some kind of shawl, mantle, coat or cloak. This is not to say she dressed for winter in the summer time but a woman had to be modest in public. It’s not habit of modern women to put on hats and gloves anymore, so it’s very much overlooked in reenactments, although the more accurate women you will see do wear hats, gloves and shawls. A shawl could be just a thin piece of painted silk or something in the summertime, just to give the illusion of modesty without overheating yourself. Outerwear in the winter became bulkier, heavier and more functional for covering and protection from the cold. Fur was a very fashionable in the winter, so even the poorest woman tried to save money for at least one piece if she could possibly afford it. Today you can use fake fur if you do winter reenacting but please do your research to make sure it looked like what would have been available in the 1860s.

Outerwear – This is a rather important thing that tends to get overlooked by modern women participating in reenactments. A woman in the 1860s never left the house without covering her head with a bonnet or hat and a pair of gloves, along with some kind of shawl, mantle, coat or cloak. This is not to say she dressed for winter in the summer time but a woman had to be modest in public. It’s not habit of modern women to put on hats and gloves anymore, so it’s very much overlooked in reenactments, although the more accurate women you will see do wear hats, gloves and shawls. A shawl could be just a thin piece of painted silk or something in the summertime, just to give the illusion of modesty without overheating yourself. Outerwear in the winter became bulkier, heavier and more functional for covering and protection from the cold. Fur was a very fashionable in the winter, so even the poorest woman tried to save money for at least one piece if she could possibly afford it. Today you can use fake fur if you do winter reenacting but please do your research to make sure it looked like what would have been available in the 1860s.

Continue on to The Lady Civil War Reenactor: Part V now….

Read More