If you know me longer than a day, you know I have a slight (read as: majorly obsessive) interest in mermaids. Believe it or not, my first exposure to them was not Disney’s The Little Mermaid. It was the Hans Christian Andersen story that Disney hijacked and turned into Ariel, Sebastian, Flounder, Scuttle and Prince Eric.

If you know me longer than a day, you know I have a slight (read as: majorly obsessive) interest in mermaids. Believe it or not, my first exposure to them was not Disney’s The Little Mermaid. It was the Hans Christian Andersen story that Disney hijacked and turned into Ariel, Sebastian, Flounder, Scuttle and Prince Eric.

Prince Eric. Pause for a 9-year-old dreamy sigh.

The Little Mermaid was originally written as a ballet and first published in 1837. Andersen’s tale is actually much darker than Disney portrayed, as were all 19th century European fairy tales happening at that time. They were used to teach children morality lessons. In the original version, the mermaid is told by her grandmother, after rescuing the prince from drowning, that when mermaids and mermen die, they turn into seafoam and cease to exist, while humans go on to Heaven and eternal life. Basically, humans have souls and merfolk do not. The mermaid is in love with the human prince, as portrayed in the Disney version, but she also longs for a soul (Disney made it into her fascination with legs), so she visits the Sea Witch for a potion that will give her legs in exchange for her tongue. This goes back to the ancient tales of sirens, also mermaids, who lured sailors with their intoxicating voices. The deal she makes with the Sea Witch is much darker than the Disney version in that the potion makes her have beautiful legs but she may never return to the sea and when she walks, it feels like she is walking on sharp swords hard enough to make her bleed. Added to that, she can only attain a soul if she finds true love’s kiss. The prince has to love her and marry her. When he does, part of his soul will flow into her (a metaphorical sexual element). If he marries someone else, the morning after the wedding, the mermaid will die, disintegrate into seafoam and cease to exist. The mermaid agrees, drinks the potion, and meets the prince, who falls in love with her. However, he is forced to marry a princess from another kingdom and the mermaid’s heart breaks. Her sisters gave the Sea Witch their hair in exchange for a knife that the mermaid must use to kill him so that his blood dripping on her feet must return her to mermaid form. The mermaid loves him and cannot bring herself to kill him. At dawn, she throws herself into the sea, where her body dissolves into foam. Instead of ceasing to exist, she feels the warmth of the sun and is told she has turned into a spirit, a daughter of the air. The other daughters of the air tell her she became one of them because she strove with all her heart to attain an eternal soul. She will earn her own soul by doing good deeds for 300 years in order to reach Heaven.

Not exactly warm, fuzzy Disney, is it?

Naturally, being a child, I much preferred the happy sing-a-long style of Disney storytelling, but being introduced to mermaids through the darker original version showed me something that felt oddly familiar. No, I’m not saying I’m a mermaid.

Or am I?

Yeah, that happened. Blame my brother for seeing that picture of me kissing Jon Knight and then slapping aviators on Eric.

But in all seriousness, I recognized as a very young girl that mermaids were special. I saw myself in them, especially after learning the Hans Christian Andersen story. The mermaid was a girl who couldn’t walk and wasn’t accepted by most of the human race. She wanted nothing more than to be loved and to continue on living with a souls just like everyone else. The story read to me as an exploration of how far a girl would go to attain the ability to walk, to lead a normal life, and to experience love without fear. In the end, she realized she couldn’t have everything she wanted and yet she became selfless by letting her love life a full life rather than sacrificing him for her own needs. Replace the fin with a wheelchair and you have basically paraplegic and quadriplegic girl in the world. It’s not a huge leap of the mind to see why someone like me would be attracted to the idea of mermaids and that story. Like every good 19th century fairy tale, I did learn a moral lesson from it but perhaps not the one Hans Christian Andersen intended. It made me think about being satisfied with the life I was given. She wasn’t satisfied with her life and her ambition made her overreach until she ended up dead without the man she loved, her family, and so forth. The 300-year sentence read to my Catholic mind as being in Purgatory. The biggest lesson of all was self-acceptance and finding the beauty of being in your own skin.

My fascination with mermaids continued into adulthood. As I developed an interest in history and the paranormal, I began to wonder where the idea of mermaids originated and whether it might be possible for them to be or have been real. An idea doesn’t just materialize out of thin air.

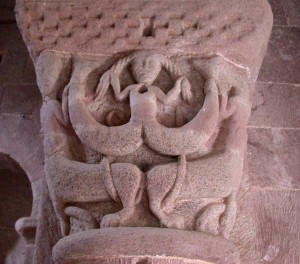

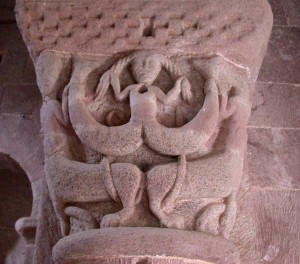

Some historical representations of mermaids.

Saint Pierre de Bessuéjouls, France (16c.).

Hortis Sanitati, 1491.

Physiologus (c. 1070).

“Monstra Niliaca Parei” from Aldrovandi Ulisse’s Monstrorum historia (1642).

England, 1230-1240.

It appears that the mermaid originated as a male god – a half-fish, half-human deity known as Oannes for the Babylonians in 5,000 BCE. Oannes represented everything positive, good and light about the sea. The female version of the Oannes deity was known as the goddess Atargatis. She was a Semetic moon goddess and is believed to officially be the first representation of a mermaid as we know her now. Fish were sacred to her, which meant that she was a woman represented with a fish tail. Stories say that Atargatis and Oannes were the parents of Semiramis, an historical queen of Babylon. This meant that Atargartis became an important fertility goddess. She also represented the darker, night forces of love and their potentially destructive power. Her cult reached as far as Britain and so began the spread of mermaids as mythological creatures throughout the world. Atargartis later evolved into the goddess Aphrodite, who was also born from the sea but then as a full human. The sea powers became her escorts, the male Tritons and the female Tritonids. Her sacred companion was a dolphin and she was a goddess of fair sailing, as well as fertility. Symbols associated with Aphrodite carried throughout mermaid mythology in multiple cultures.

The Greeks were largely responsible for the evolution of an occasional mermaid deity into an entire race of merfolk. Aware of the abundant life in the oceans, the Greeks knew how to tell sea tales. An incestuous union between brother and sister, Oceanus and Tethys, produced 300 sea-nymphs called Oceanids, along with a great many other sea creatures meant to depict its fertility. Some of the creatures produced were Metis, who became mother of Athene by Zeus. One known as Euromyne was depicted as a mermaid in a statue at Phigalia. Further issue from Oceanus and Tethys was Doris, who became the wife of another sea-god, Nereus, who then produced 50 more sea-nymphs known as Nereids. Among these were Thetis, mother of Achilleus, and Amphitrite, who became the wife of the later sea-god Poseidon, and bore the race of Tritons.

I know, it’s all very sordid and confusing. I almost need to draw a map.

By 80 CE Pliney, the Nereids sea-nymphs became synonymous with mermaids, while Tritons were mermen. The original sea-gods were Wise Old Men of the Sea in keeping with the tradition begun by Oannes, but the Tritons were a lustful and rapacious lot, fond of assaulting unwary sea-nymphs and human women alike. The Nereids, on the other hand, were protective of sailors, and reserved their beautiful singing voices to entertain their father, unlike the dangerous Sirens who ensnared sailors with their enchanting voices and lured them to watery deaths. The Sirens were originally bird-women related to the Egyptian Ra, or soul birds, demons of death sent to catch souls. But the Sirens eventually became synonymous with mermaids; thus the mermaids acquired their unpleasant reputation for drowning sailors. This evil aspect can also be traced to a certain degree as stemming from Greek sea-monster propaganda, promoting a fearful image of the sea to discourage commercial rivals in shipping and colonization.

Whilst the Sirens tempted Odysseus with supreme knowledge, a god-like attribute, later the emphasis shifted to worldly temptation. Thus the mermaid/siren symbol was used by the Medieval Church as embodying the lure of fleshy pleasures to be shunned by the God-fearing. The mermaid became a victim of the repressive sexual attitudes of the Christian Church. Mermaid carvings figured prominently in church decorations in the Middle Ages, to symbolically serve as a vivid reminder of the fatal temptations of the flesh. These rapacious soul-eaters (the legacy of the bird-sirens) were of course not considered to have souls of their own. Thus, the legends of the more highly-principled mermaids, anxious to acquire souls, arose.

Whilst the Sirens tempted Odysseus with supreme knowledge, a god-like attribute, later the emphasis shifted to worldly temptation. Thus the mermaid/siren symbol was used by the Medieval Church as embodying the lure of fleshy pleasures to be shunned by the God-fearing. The mermaid became a victim of the repressive sexual attitudes of the Christian Church. Mermaid carvings figured prominently in church decorations in the Middle Ages, to symbolically serve as a vivid reminder of the fatal temptations of the flesh. These rapacious soul-eaters (the legacy of the bird-sirens) were of course not considered to have souls of their own. Thus, the legends of the more highly-principled mermaids, anxious to acquire souls, arose.

Apparently, one method for a mermaid to gain a soul was to marry a human being; the best known form of this legend is Hans Christian Andersen’s ‘Little Mermaid’. But similar legends abound in the folklore of many countries. Celtic mythology included the sanctified Liban, a young woman drowned and transformed into a mermaid, who after 500 years, enlisted the aid of the Irish St. Comgall to save her soul; also the Mermaid of Iona who wept many bitter tears over her inability to leave her ocean home to gain her promised soul. St. Patrick allegedly had a custom of transforming pagan women into mermaids, adding to the marine population in Ireland.

France has the legends of Melusine and Undine, both water-spirits who married noblemen. These mixed marriages in legend almost invariably fail miserably, with the unhappy mermaid ultimately unable to abandon her ocean element. In Germany, on the Rhine River, they had their Lorelei or Nix, a beautiful blonde siren who sat on a cliff luring boatmen to their deaths with her songs, in traditional style. There are the ‘morgens’ of Brittany, seemingly descendants of Morgan Le Fay, the sorceress of Arthurian legend. These creature lure all who come too near, down to their gold and crystal underwater palaces. In Norway, the ‘havfrau’ portends imminent disaster if sighted sitting on the surface of the water combing her long golden hair with a golden comb. The Japanese have their mermaids known as Ningyo.

In fact, the mermaid archetype is so widespread among cultures that one may conclude it is very ancient, and fulfills a particular need in the human collective consciousness. The mermaid in our culture is the most persistent and pervasive symbol of the old Goddess energy that represents women, particularly the mysterious, life-generating element. The Christian Church, in promoting the ideas that mermaids were dangerous temptresses and had no souls of their own, was actually stating deeply-held beliefs about all women, much as in the case of the witchcraze, when harmless old women were put to death by burning or hanging for practicing traditional herb-lore; this being the province of women it was destroyed by the Church in support of male domination. This beautiful, helpful and compellingly attractive goddess-mermaid has been stripped of all her spiritual qualities; hence, the stories involving the mermaid’s soul could never end happily. They emphasized the supposed faithlessness and inconstancy of women, the danger of their attraction, and the unlikelihood of their gaining humanity.

In Elizabethan times, the mermaid was used as a symbol of prostitution, and thus, popularly applied to Mary Queen of Scots, as Queen Elizabeth’s hated rival. Shakespeare, in the Midsummer Night’s Dream, included these lines supposedly referring to Mary, five years after her execution:

‘Thou rememberest

Since once I sat upon a promontory,

And heard a mermaid on a Dolphin’s back

Uttering such dulcet and harmonious breath,

That the rude sea grew civil at her song;

And certain stars shot madly from their spheres,

To hear the sea-maid’s music.’

The ‘mermaid’, ‘sea-maid’ meaning Mary; a dolphins back’, she married the Dauphin of France; ‘the rude sea’, the Scotch rebels; ‘certain stars’ referring to the Earls of Northumberland and Westmoreland and the Duke of Norfolk; ‘shot madly from their spheres’, revolted from Queen Elizabeth, enchanted by Mary’s feminine qualities. These lines may been disguised flattery; but it seems unlikely since Mary was dead, and also due to the prostitution symbolism of the mermaid at the time. More likely it was directed at Elizabeth, Shakespeare’s patroness, in the sense of censuring the behaviour of her rebel nobles. The mermaid was a popular poetic and allegorical symbol in Elizabethan theatre.*

But can mermaids be real? From a cryptozoological standpoint, that’s a tough question to answer and can only be based in theory and possibility, much like the New England sea serpent or the Loch Ness monster. The cryptozoology world largely ignores mermaids because the very idea sounds rather far-fetched. However, I see mermaids as no more far-fetched than werewolves or the alleged dinosaur species that still exist in Africa. The sheer number of first-hand mermaids sightings for thousands of years does make some cryptozoologists stand up and take notice though.

The different between fairy tale mermaids and cryptozoological mermaids is described by people who have allegedly seen them. They are not strictly human from the waist up with verbal speech, beautiful hair, etc. They are typically described as nonverbal, having black or green hair, and having fishy characteristics above the waist.

There are several different scientific theories that have been put forth to explain mermaids and mermen. One idea is that merfolk are animals. They might be some variety of undiscovered fish that has a top half that simply looks human, or they might be a variety of primate that evolved to a half-aquatic lifestyle. Unfortunately, not much evidence has come forth to support either idea. If merfolk exist and are animals, they must be incredibly rare, for science has never managed to get a dead body despite the fact that merfolk are supposed to love hanging about near shore, where capture should be easy and bodies would probably wash onto the beach.

Another idea holds more promise, but strays outside the normal confines of cryptozoology. According to this idea, merfolk are actually intelligent aliens. This idea is supported by the earliest merfolk legends, which describe semi-aquatic “gods” that came from the stars. If this idea were true, merfolk would be the descendants of these ancient aliens, perhaps ones that had been genetically modified to make them look more human and thus get along better with their human subjects. At some point, the set-up for playing gods collapsed and these remnants were stranded here to live out their lives apart from humans. This would explain why we don’t capture mermaids or find bodies, because an intelligent race, unlike animals, would have the ability to prevent such occurences. Unfortunately, even though this idea makes for an attractive story, it doesn’t have much going for it other than some really old legends.

Other explanations lean more towards the supernatural and, thus, are of less interest to cryptozoologists. Mermaids are explained as spirits of the water, as shapeshifters, as a subcategory of fairies, even as a type of demon.

In addition to the various speculations in cryptozoology as to whether mermaid reports might represent a new species of some sort, there is another connection between mermaids and cryptozoology. Some reports of mermaids link them to sea serpents and lake monsters. There are several ways this link can be formed. Firstly, there are legends about mermaids and other water spirits commanding sea monsters and lake monsters. Secondly, a few mermaids are reported to have extra-long tails, like sea serpents, instead of a fishy tail. Thirdly, a few rare mermaids are supposed to be shapeshifters who alternate between a mermaid form and one that resembles a sea serpent. For example, Morag, the legendary monster of Loch Morar, is said to appear in one of two forms. One is a beautiful blond mermaid, the other is a many-humped monster resembling Nessie. According to local lore, Morag appears in her monster form when someone is about to die.**

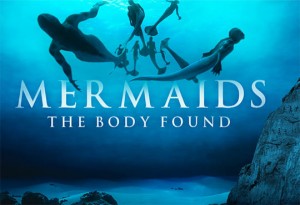

Recently, Animal Planet created a “documentary” called Mermaids: The Body Found. I have seen a shocking number of people who actually believe this program depicted a truthful story. It was not. The program was explained afterward as being a “what if” scenario. The reasons escape me as to why Animal Planet would produce something intentionally fake but they did and it has a lot more people wondering if mermaids could be real. It appears to me that the people who made the program did it from a heavily cryptozoological standpoint because the theories and appearance of mermaids in it seem to have been directly lifted from the cryptozoologists who are willing to study their possibility. Let me state here for my readers who might be confused that this program was fiction. None of it actually happened, although the theories they presented are widely discussed among the mermaid minority in the study of cryptids.

Do I think mermaids exist?

Do I think mermaids exist?

I don’t know.

I would like to think they might exist in some form just like people swear aliens, Bigfoot, werewolves, Nessie, etc., all exist. There are thousands of years of mermaid sightings all over the world, so I find it hard to believe all of those people were liars. I don’t actually think King Triton, Ariel and her sisters are swimming around the Caspian Sea, but I do think the possibility exists that a human-like species could have taken to the sea thousands of years ago while we stayed on land. There are a lot of different types of monkeys and apes, so who is to say there weren’t different types of humanoid species as well? I certainly don’t think they look/looked like Ariel either. I think they would resemble fish with human features that would make us relate to one another despite the inability on their part to speak. Mermaids may have existed at some point but may be extinct or severely endangered now. And truthfully, I hope they are never found. If they were found, they would be hunted to death.

For now, it’s nice to read the stories and imagine what might be.

And be sent hilarious things like these.

*Historical text borrowed from an article called Shadows of the Goddess – The Mermaid, by Scarlett deMason.

** Cryptozoological text borrowed from http://www.newanimal.org/merfolk.htm

Read More