>

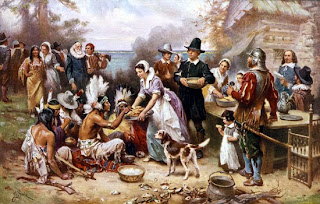

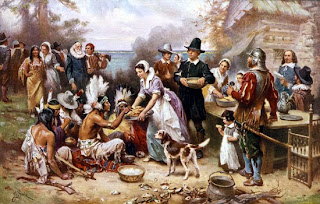

The truth about the first “Thanksgiving” in 1621 is actually a myth conjured, as much of American history is, by white men. In truth, there was no display of interracial harmony between the Pilgrims and the Indians. Various stories about the origins of the first Thanksgiving exist ranging from August through October of 1621 and all of them involve the Pilgrims celebrating the conquering and slaughter of hundreds of Indians living in what is now Massachusetts. Most likely, the myth of Indians and Pilgrims coming together was inspired by a feast given for Squanto, an Indian who was captured, made a slave, and later negotiated treaties. He was the only Indian present at the feast. Another “day of Thanksgiving” was declared after the slaughter of four hundred Indians as well.

The truth about the first “Thanksgiving” in 1621 is actually a myth conjured, as much of American history is, by white men. In truth, there was no display of interracial harmony between the Pilgrims and the Indians. Various stories about the origins of the first Thanksgiving exist ranging from August through October of 1621 and all of them involve the Pilgrims celebrating the conquering and slaughter of hundreds of Indians living in what is now Massachusetts. Most likely, the myth of Indians and Pilgrims coming together was inspired by a feast given for Squanto, an Indian who was captured, made a slave, and later negotiated treaties. He was the only Indian present at the feast. Another “day of Thanksgiving” was declared after the slaughter of four hundred Indians as well.

Americans have been brought up on the myth of Thanksgiving since the beginning but it was never an official national holiday. It evolved into a feast contained to New England celebrating the yearly harvest and each colony (eventually states) had their own days to celebrate the “day of Thanksgiving”. Each colony operated on its own government, as did each state after the American Revolution. They had their own currencies, governments and holidays, operating as tiny countries part of a collective group, rather than a united country of different states. Outside of New England, the “holiday” hardly existed, although celebrating harvests was common everywhere. The menu was similar for the harvest season throughout New England and not totally unlike our Thanksgiving menu today but as with all food in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it depended on what could be obtained locally. Seafood was on the menus in coastal areas, for example.

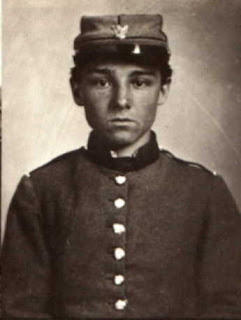

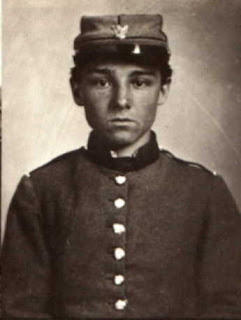

As the Civil War raged on in the mid-1860s, President Lincoln’s popularity was comparable to President George W. Bush today. The war was unpopular and scorn was prevalent as more soldiers were killed. Thousands of men were butchered in battles. Let me give an example. I believe approximately three thousand people were killed on 9/11. At the battle of Antietam, there were 22,000 killed, wounded and captured in one day. At the battle of Gettysburg, which was three days, there were 53,000 casualties. Between April 1861 and April 1865 — four years — approximately 662,000 of the 2 million men and women who fought in the war were killed. Take what you felt on 9/11 and multiply it by four years and over half a million lives snuffed out at the average age of 25, with approximately 100,000 under the age of 15 in the Union Army. President Lincoln began thinking of how he could improve his image and unify the country. His entire goal with the Civil War was to unite the country.

As the Civil War raged on in the mid-1860s, President Lincoln’s popularity was comparable to President George W. Bush today. The war was unpopular and scorn was prevalent as more soldiers were killed. Thousands of men were butchered in battles. Let me give an example. I believe approximately three thousand people were killed on 9/11. At the battle of Antietam, there were 22,000 killed, wounded and captured in one day. At the battle of Gettysburg, which was three days, there were 53,000 casualties. Between April 1861 and April 1865 — four years — approximately 662,000 of the 2 million men and women who fought in the war were killed. Take what you felt on 9/11 and multiply it by four years and over half a million lives snuffed out at the average age of 25, with approximately 100,000 under the age of 15 in the Union Army. President Lincoln began thinking of how he could improve his image and unify the country. His entire goal with the Civil War was to unite the country.

In November 1863, the first national Thanksgiving day was declared by President Lincoln in his effort to boost the morale of the people and remind them of why they went to war in the first place. He took the autumn harvest celebration from the New Englanders and turned it into a national holiday steeped in religion, family and remembering family and friends lost during the war.

In November 1863, the first national Thanksgiving day was declared by President Lincoln in his effort to boost the morale of the people and remind them of why they went to war in the first place. He took the autumn harvest celebration from the New Englanders and turned it into a national holiday steeped in religion, family and remembering family and friends lost during the war.

The mythical story of the Pilgrims and Indians sitting down together at the same table was a subconscious effort to look toward the future of the United States and the Confederate States sitting down at the same proverbial table to become a singular nation once again. Before the Civil War, as it is known, people referred to the country as, “The United States are…” and after the reconstruction of the nation, it was referred to as, “The United States is…” So because of President Lincoln, we now celebrate Thanksgiving on the same day every November throughout the nation.

Wild fowl was the main thing on the menu for the Thanksgivings of old and that could be turkey, duck, pheasant and so on. In the earliest days of Thanksgiving, stuffing was called dressing and consisted of stale bread, cornmeal and seasonings. As the settlement of the colonies progressed into a new country and into the nineteenth century, people got more adventurous with cooking and Thanksgiving became an elaborate meal with multiple courses. It became popular to stuff turkey with chestnuts, dried cranberries, oysters, sausage or locally grown fruit (meaning it would be different depending on the part of the country).

Besides wild fowl stuffed with various things, the nineteenth century New England Thanksgiving would have also served potatoes and sweet potatoes just as we do today, along with turnips or carrots. People near the ocean almost always incorporated oyster and fish dishes into their meals as well, no matter the social or economic class. Dessert would have included pies like we eat today, such as pumpkin and mince pie, Indian pudding, fruit, nuts and berries. Since there was very little ability to refrigerate food in the nineteenth century, they ate nothing but leftovers until the food was gone. Not a morsel was wasted if it was at all possible. Cookbooks and recipes in magazines at that time showed people how to make new meals out of their Thanksgiving leftovers like Deviled Turkey, Turkey in Savory Jelly and Thanksgiving Turkey Pot Pie.

This menu is based on a Thanksgiving dinner from the 1880s.

* Oyster Bisque

* Roast Turkey with Chestnut Stuffing

* Giblet Gravy

* Mashed Potatoes

* Butternut Squash

* Glazed Turnips

* Pickled Beets

* Whole berry cranberry sauce

* Rolls

* Pumpkin Pie

* Mince Pie

* Whipped Cream, lightly sweetened

* Coffee, Tea, Punch

This menu came from a 1905 Thanksgiving dinner, which was technically the Edwardian period after the Victorian period.

* Oysters on the half-shell with cocktail in pepper shells.

* Radishes, celery, salted nuts.

* Clear consommé with tapioca.

* Filet of flounder with pimentos and olives; dressed cucumbers.

* Roast turkey; cranberry jelly in small molds; creamed chestnuts; glazed sweet-potato.

* Cider frappé in turkey sherbet-cups.

* Quail in bread croustades; dressed lettuce.

* Blazing mince pie.

* Cheese with almonds; wafers.

* Angel parfait in glasses; small cakes; coffee.

Read More

This lovely ballgown on the left is today’s dressgasm but it’s not the whole dress, so I thought I would use today to talk about interchangeable dresses. This piece came from another eBay auction over a year ago from one of my favorite sellers but I don’t know a lot about the history of it, where it came from or who wore it originally.

This lovely ballgown on the left is today’s dressgasm but it’s not the whole dress, so I thought I would use today to talk about interchangeable dresses. This piece came from another eBay auction over a year ago from one of my favorite sellers but I don’t know a lot about the history of it, where it came from or who wore it originally.