Review of Part I

Review of Part I

In the first part of The Lady Civil War Reenactor, I gave an introduction about what should be expected at most reenactments for women, why people choose to participate in reenactments, and a list of vocabulary commonly spoken by people in the reenactment community. I also asked that if people had questions, to post them in the comments and I would go over them in the next blog (this one). Here are the questions I got on the last blog.

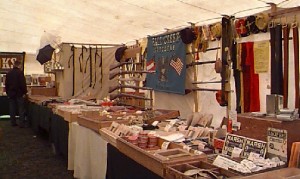

How is currency handled at events?

It’s virtually the same as going to a fair or anything of that nature. Sutlers usually take cash, checks or credit cards, although there are some that don’t take credit cards, but they will tell you up front. Food vendors are the same. Reenactor registration is sometimes done online beforehand with credit cards but is also done in person at the beginning of the event usually with cash. The best advice for attending reenactments whether you are a spectator or a reenactor is to bring both cash and credit cards to be prepared for either.

What do you wear to bed?

If you are a reenactor, that depends on your level of authenticity. Some reenactors will choose to wear 21st century clothes to bed. A lot choose to stay in their 19th century impression for the duration of the reenactment, which means women would sleep in period correct nightclothes. I will discuss that in greater detail in a future blog.

How are tents set up?

That depends on the people running the events and the people in charge of your various reenacting organizations. They’re usually set up in rows like you would see in 1860s photographs of army camps. Tents must be period correct, made of white canvas with wood poles, and such things can be purchased from various sutlers. Again, I will discuss that in greater detail in a future blog about equipment and what you will need to bring with you.

Can you have a fire?

In the vast majority of cases, yes. Reenactments are very rarely held within the boundaries of national parks, which would not allow campfires. The majority of reenactments are held on private farms nearby or anywhere else where they can borrow the land for a weekend. A lot of event organizers will provide firewood, although it’s not always provided. It just depends on who is organizing it and what size of reenactment we’re talking about here.

How do you get water?

Again, it depends on who is organizing the reenactment and what size of reenactment were talking about, but water is either provided by the organizers or people by water beforehand and bring it with them. It’s like modern-day camping. A lot of campgrounds don’t provide water, so you just go to the nearest store and buy those milk gallon jugs of water or bottled water or whatever kind of water you choose. Depending on your level of accuracy, you should make an effort to conceal the fact that you are bringing plastic jugs into camp.

Building Your Impression

As you may remember from the last lesson in the vocabulary section, your impression is the type of person you are portraying from the Civil War. Building and impression is basically the same thing as building your character in a play. The best reenactors have back stories for who they are, they speak in first person, and they can tell you everything about why they’re wearing what they’re wearing, why they’re doing what they’re doing, and how it was done in the 1860s. Especially for civilian reenactors, this is extremely important to consider. As civilian reenactors, we are not always seen as necessary by the military reenactors, and therefore, a lot of it seemed to work harder at what we do as far as doing it correctly. If you’re just beginning in the reenactment hobby, the worst thing you can do is go shopping on eBay, choose a dress just because it looks pretty and throw it on for the next upcoming event. Reenacting can be a bit of an expensive hobby, so it’s really important to do the proper research before you make any purchases whatsoever. A lot of people who are new to it usually end up buying a lot of junk in their first year that will be discovered to be inaccurate or completely unnecessary. My goal is to help you avoid making those common mistakes so that you don’t waste money in your first year.

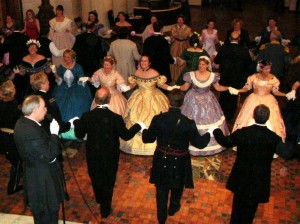

If you think you’re going to look like Scarlett O’Hara at every reenactment, it’s best to just put that idea out of your head right now. A lot of women who are new to the hobby enjoy the romance and grandeur of Gone with the Wind and use it as the Bible of what Civil War reenacting should be for them. In reality, the wealth portrayed in Gone with the Wind was really only a portrayal of the top 1% of Southern American society in the 1860s. Additionally, the costuming in that film, while beautiful, is really just a 1939 interpretation of the 1860s, which is ridiculously inaccurate for the time. You would not see women dressed like Scarlett O’Hara from the 1860s and if Vivien Leigh was to go back in time in her Scarlett costume, other women would look at her like she was an alien. I’m only mentioning Gone with the Wind because of the amount of women I see at reenactments trying to emulate that movie. Only in recent years have I seen women really try to get away from emulating North and South as well, or what I like to call Civil War Barbies. So let me stress this point to you very clearly:

If you think you’re going to look like Scarlett O’Hara at every reenactment, it’s best to just put that idea out of your head right now. A lot of women who are new to the hobby enjoy the romance and grandeur of Gone with the Wind and use it as the Bible of what Civil War reenacting should be for them. In reality, the wealth portrayed in Gone with the Wind was really only a portrayal of the top 1% of Southern American society in the 1860s. Additionally, the costuming in that film, while beautiful, is really just a 1939 interpretation of the 1860s, which is ridiculously inaccurate for the time. You would not see women dressed like Scarlett O’Hara from the 1860s and if Vivien Leigh was to go back in time in her Scarlett costume, other women would look at her like she was an alien. I’m only mentioning Gone with the Wind because of the amount of women I see at reenactments trying to emulate that movie. Only in recent years have I seen women really try to get away from emulating North and South as well, or what I like to call Civil War Barbies. So let me stress this point to you very clearly:

Do not use movies or television as a reference for what you should be using to build your impression.

So what should you use to build your impression if movies and television are out? You need to get used to looking for primary sources. In research terms, a primary source is material directly from someone living in the 1860s, while a secondary source is material about the 1860s but removed from it. Diaries, letters, photographs and paintings are primary sources. Books written by modern authors about those things are secondary sources. My advice to you from the beginning is to learn to depend on primary sources so that when someone asks you where you got your inspiration, you can direct them to someone who actually lived in the 1860s instead of an expert who could misinterpret information or wasn’t even there.

The primary thing you should consider when building the foundation of your impression is what kind of reenacting organization you plan to join. Pennsylvania reenactors, especially women, are not going to look the same or have the same backgrounds as, say, rural Georgia reenactors. You also don’t want to completely go against the grain of whichever organization your choosing to join. You wouldn’t, for example, show up in a refugee group dressed like the Queen of Sheba. On the other hand, you wouldn’t look like a refugee if you were portraying a woman married to, say, a Union general. The environment in which you’re going to do most of your reenacting is really going to determine what kind of impression you build from the beginning. In the way that people from different parts of the country look and act differently today, they also looked and acted differently back then as well. Your best bet, if you are completely new to it, is to go to your local library or historical society – actually the historical society is probably the best bet – and do some research on what kind of women were living in your area during the Civil War because those were the wives, mothers, sisters and daughters of the fighting men. Were they mostly farmers’ wives? Were they city women? Was the area made up of poor people? Rich people? You probably will join a unit in your area who has already done research of that nature, so you will probably portray average people within that unit.

Choosing to be an independent reenactor – someone who is not affiliated with any unit or organization – can be very difficult but it also allows you more freedom to choose what kind of impression you want to do. The reason why it’s more difficult an independent reenactor is because most national reenactments require people to be part of the unit and register as a unit. If you are considering being an independent reenactor, you will almost certainly need to find a unit that will allow you to register with them for the national events. People who choose to do it independently are usually portraying somebody more well-known from the time. For example, I’m an independent reenactor and I portray Fanny Chamberlain. Fanny would not have been tagging along with Georgia regiments since she was living in Maine at that time, which is why I’m not officially affiliated with any local unit or organization. I also have the ability to portray an average Georgia woman should I need to join a local unit at some point. I do not recommend choosing one specific person to portray if you are just beginning in reenacting unless you have someone taking you under their wing and leading you by the hand because if you run into anyone who is a “fan” of that person you’re portraying, and you do something wrong, you can earn a bad reputation really fast. When I’m doing bigger national events and I’m planning to be Fanny, I actually have to dye my hair dark because she was not a redhead. I don’t like to wear wigs, although some women do, but I think most wigs end up looking fake and tacky like you just playing dress-up (I will probably take some heat for that but it’s just how I feel). So unless you are portraying something completely out of the ordinary for your local area, I would not go the independent route. I would join a unit. There are usually multiple units in every state and you will have the luxury of choosing which one is the best fit for you.

Choosing to be an independent reenactor – someone who is not affiliated with any unit or organization – can be very difficult but it also allows you more freedom to choose what kind of impression you want to do. The reason why it’s more difficult an independent reenactor is because most national reenactments require people to be part of the unit and register as a unit. If you are considering being an independent reenactor, you will almost certainly need to find a unit that will allow you to register with them for the national events. People who choose to do it independently are usually portraying somebody more well-known from the time. For example, I’m an independent reenactor and I portray Fanny Chamberlain. Fanny would not have been tagging along with Georgia regiments since she was living in Maine at that time, which is why I’m not officially affiliated with any local unit or organization. I also have the ability to portray an average Georgia woman should I need to join a local unit at some point. I do not recommend choosing one specific person to portray if you are just beginning in reenacting unless you have someone taking you under their wing and leading you by the hand because if you run into anyone who is a “fan” of that person you’re portraying, and you do something wrong, you can earn a bad reputation really fast. When I’m doing bigger national events and I’m planning to be Fanny, I actually have to dye my hair dark because she was not a redhead. I don’t like to wear wigs, although some women do, but I think most wigs end up looking fake and tacky like you just playing dress-up (I will probably take some heat for that but it’s just how I feel). So unless you are portraying something completely out of the ordinary for your local area, I would not go the independent route. I would join a unit. There are usually multiple units in every state and you will have the luxury of choosing which one is the best fit for you.

There are some important things to remember when building your impression. A woman in the 19th century would not have had a job unless it was absolutely life or death necessary, especially if she was married and raising a family. That was her job – raising the family. Women who did work were looked down upon because it meant putting themselves out there in the public in a time when women were supposed to be mostly confined to the home. So as a female in the 1860s, your main concern would have been the condition of your family and what you could do to deserve that family. A lot of women, especially officers’ wives, began looking after the regiments the way they look after their own families. They sent food when they could, they sent new clothing, they nursed wounded and sick men back to health, and so forth. Higher society women would not have gotten their hands dirty, so to speak, so they were more interested in raising money for the cause with bazaars, auctions and things of that nature.

On average, women were not as educated as men. A female’s education was based on what she would need to run the household. Illiteracy was much more common in the 19th century than it is now, especially among women and people of the lower classes. An upper-class woman of the 1860s would have been able to speak Latin, French, Italian, etc., she would have been able to embroider, she would have been able to manage domestic servants (or slaves depending on the part of the country). A lower-class woman of the 1860s would have far less of an education but she would have been able to cook, sew, look after livestock, be a natural nurse, midwife, and she would have had far more practical skills out of necessity.

The reason why military reenactors kind of grumble and look down upon civilian reenactors is because there weren’t so many civilians following the armies around during the Civil War. Women who followed the armies were occasional visitors of officers’ wives, sometimes they were nurses later in the war, they were laundresses, and they were also prostitutes. Average women didn’t have the luxury of following their husbands into the army because they had to manage everything at home in their husbands’ absences. So in this regard, Civil War reenacting does kind of fudge history because women today are not willing to avoid participation just because there weren’t so many women of that time around the armies. Whenever possible, it is extremely important to portray women as they were when they did follow the armies by being willing to behave and not such glamorous roles of laundresses and nurses. Not every woman can be an officer’s wife, for example, and that seems to be what a lot of new women want when they start participating in the hobby. It is partially our responsibility as reenactors to educate the public, so there needs to be a willingness to fill the not so glamorous roles and be more accurate in what really happened.

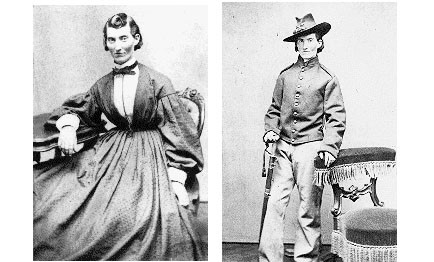

That brings me to female reenactors portraying soldiers. This is a little bit of a controversial topic. I can’t tell you how many new women coming into the hobby proudly declare that they will be disguised as males and joining the fighting because it’s much more fun. It makes me cringe every time I see a female reenactor on the battlefield. It’s not because women didn’t fight in the war. There were women who fought in the war but far less than what is being portrayed by reenactors. High estimates in the Confederate army placed female soldiers at only 250 while estimates in the Union Army place female soldiers at 400. Considering this war was made up of roughly three million soldiers, we are talking about a very, very small percentage of females disguised as men. The amount of women portraying soldiers in reenacting today makes tourists think that the numbers were much higher, which is not at all accurate.

The other part of female reenactors portraying soldiers is that they are easily recognizable as females. In the 1860s, women who were caught in the military were sometimes jailed, but at the very least, they were kicked out of the army and sent home. Being recognized, to them, was a matter of life and death, so they did everything humanly possible to conceal their identities. When it’s done accurately, you should not be able to tell the difference between a female and, say, a teenage boy soldier. But the women who are doing it now are very easily spotted because they’re not concealing themselves enough. I am personally of the attitude that if you’re going to do something, you should do it right. So when women come to me saying they want to be a soldier, I usually try to talk them out of it because there are so many doing it already. If more excitement is what’s desired, my suggestion is doing an impression based in espionage.

Determining what kind of person you are going to do for your impression (again, you don’t need to do someone who actually lived – you can build your own based on your research) is going to determine what kind of equipment you bring with you, what kind of clothing you wear, how you speak, what sort of back story your building, and so forth. You need to keep in mind who you are in the present as well because a 35-year-old woman is not going to portray a 16-year-old girl, for example. Here is a questionnaire that is designed to help you flesh out your impression, much like you would flesh out a character in a novel or a play. This is designed to give dimension to your portrayal and help you understand what kind of things you need as far as clothing and equipment.

Fleshing out Your Impression Questionnaire

Directions: answer this questionnaire as if speaking in your first person persona between 1861 and 1865. This will require some research into the type of people who lived in your area at that time.

1. How old are you?

2. What is your marital status?

3. Where do you live? (City home, farm, boarding house, refugee, etc.)

4. What is your financial status?

5. Which of your male relatives are serving in the war? Confederate or Union?

6. Have you or will you volunteer in any relief societies?

7. What is your religious background?

8. What is your educational background?

9. Do you have any special talents? (Painting, embroidery, music, etc.)

10. Describe your daily routine.

11. Describe your feelings on the war, slavery, the current political climate, etc.

Continue on to The Lady Civil War Reenactor: Part III now.

Read More