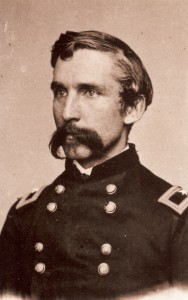

Today Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain would have been 184-years-old. He was born on September 8, 1828, in Brewer, Maine. He was the oldest of five children in any very religious and sometimes rather strict family. After largely achieving a self-education, he attended Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, and graduated in 1852. He then went on to the Bangor Theological Seminary where he crammed four years of education into three years. Originally he wanted to become a Congregationalist minister but I don’t think he ever really fully committed to that idea enough to make it his lifelong career. The woman he married, Fanny Adams, sort of pushed him away from the ministry because she had been raised by a minister and knew how difficult that kind of life was on the family because he would always be attending to the needs of his congregation over his own. So when they married, he became a professor at Bowdoin where he remained until the Civil War. Those with quiet years, between his marriage and the war, when he had a steady job and raised his small children.

Today Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain would have been 184-years-old. He was born on September 8, 1828, in Brewer, Maine. He was the oldest of five children in any very religious and sometimes rather strict family. After largely achieving a self-education, he attended Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, and graduated in 1852. He then went on to the Bangor Theological Seminary where he crammed four years of education into three years. Originally he wanted to become a Congregationalist minister but I don’t think he ever really fully committed to that idea enough to make it his lifelong career. The woman he married, Fanny Adams, sort of pushed him away from the ministry because she had been raised by a minister and knew how difficult that kind of life was on the family because he would always be attending to the needs of his congregation over his own. So when they married, he became a professor at Bowdoin where he remained until the Civil War. Those with quiet years, between his marriage and the war, when he had a steady job and raised his small children.

Many of you already know about his service in the war – being commissioned lieutenant colonel of the 20th Maine, then promoted to colonel just before Gettysburg, and then receiving the only battlefield commission of the war by General Grant at Petersburg, followed by being selected by General Grant to receive the formal Confederate surrender at Appomattox. He was wounded six times during the war and once was nearly mortal. Many horses were shot out from under him in battle as well.

After the war, he was elected Governor of Maine four times in the Reconstruction years. There was talk of running for the Senate or even President but Mrs. Chamberlain absolutely refused to spend many more years parted from her husband and father of her children. The long separations took a toll on their marriage and it reached a point in 1868 that could have resulted in divorce. Instead, he agreed to leave home and they had a separation for a year before they were able to work on their marriage. Later, he became President of Bowdoin College for twelve years with popularity going up and down as he slowly changed the school into more of a military facility. Bad real estate investments and financial trouble prevented him from retiring in old age as a man usually did in his position, so he worked as a surveyor in Portland, Maine. He also toured and lectured about the war, published books, and worked with veterans to establish monuments, funding and so forth.

In 1914, he passed away after a lengthy illness related to the wound that nearly killed him in the Civil War. He lived into his 80s and saw his grandchildren grow.

I’m not really here to write another biography about him because there are plenty of books that do a much better job of that than I could. I just wanted to give people a basic idea of his life in case they are not familiar with him or other historical figures of the Civil War. After he died, he sort of slipped into history until Ken Burns heavily drew from his writing for his documentary on the Civil War, followed by Jeff Daniels portraying him in the films Gettysburg and Gods and Generals. Since then, he has become both a very popular figure in American history and a misunderstood and, at times, a villainous figure to people who don’t understand him or what he did with his life. He has been accused of everything from being a champion of veterans and quite humbled to being egotistical and rewriting his own history to make himself look like the savior of the Union. It really just depends on who you ask. Such tales are common with any historical figure who becomes popular in modern times. They are always picked apart and scrutinized, leading to some image of what we think they were as opposed to who they really were in their lives.

It used to bother me quite a lot that people couldn’t possibly know him the way I did. Given my unusual position of having rather intense past life memories of being married to him, it has taken me a while to reconcile myself to the idea that my contemporaries now are never going to see him through my eyes back then. We had an extremely complicated relationship that I have written about at length in different blogs around here, so I don’t really feel the need to repeat myself that much. I even published a book about my reincarnation experiences concerning this family and I do have plans to release an extended version of that book because a lot has happened since the original publication date. I used to feel the need to argue with people who didn’t understand my position or in believing that kind of thing but I have grown so much since I came to terms with my own history that it really doesn’t matter anymore if people understand or not. When everything is said and done, the only thing that matters at the end of a life is the relationship you had with your companion just between the two of you and no one else. There is a lot of freedom in no longer needing to prove yourself to outsiders.

Since I came to terms with who I was to him, I have found myself sort of using his birthday as a marker to examine my own progress in spiritual development. Lawrence, in his lifetime, used his birthday each year to write a letter to his mother and talk about how he has changed and developed from the last year or the years before that. I sort of follow his example and continue the tradition in my own way. It is my opinion that spontaneous past life memories, whether they occur in childhood or adulthood, are neither spontaneous nor accidental. Those of us who have such strong cases usually have leftover things that need to be learned which were incomplete or unresolved from the previous life. We’re also here to help people understand that life doesn’t end with death and neither does love. I no longer have the nightmares about Civil War military hospitals and different kinds of insecurities and abandonment that plagued me in that lifetime because I stopped ignoring what was happening to me and I pushed myself to understand what happened, why it happened, and why it was affecting me in this lifetime so much. As Fanny, I died with a lot of demons that most people don’t even know about today and only a few historians have touched on, but also, myself as Fanny had leftover demons from the lifetime prior to the 19th century that were never resolved. So what you have a snowball effect getting bigger and bigger until it became impossible to ignore here in the 21st century. This lifetime has been about melting that snowball and exorcising the demons built up from multiple lifetimes in order to make my future easier to swallow and not so complicated.

This September 8 is remarkably different from previous September 8 days for me. In the beginning, I would have just been coming out of the summer of nightmares. It was a bit of a cycle for me throughout my life to have repeating nightmares of the summer of 1864 when he was nearly killed. Something about the heat and humidity of the South triggered it for me and I spent many summers having bouts of insomnia and bouts of nightmares. When I began writing my book about my reincarnation experiences and putting the energy into understanding why things happened, the nightmares slowed down and eventually stopped. I don’t think I’ve had a nightmare for about maybe two or three years. That’s the longest time I’ve gone without having a nightmare and I have no desire to go back to reliving it. To me, it’s a victory. I let go of the trauma. I now have the ability to read books about Petersburg and I’m okay with setting foot in the state of Maryland (he recovered in Annapolis) without feeling panic in the pit of my stomach. In many ways, I’m glad he’s not reincarnated right now because I was not the one who was almost killed and I suffered for years with traumatic flashbacks. Had he come back soon, he would have had much more confusing and debilitating flashbacks. If we are ever together again, my idealistic nature likes to believe that because I’ve already been through it – uncovering the history and dealing with the flashbacks – that I could have the instincts to help him deal with it even if I don’t remember what I did in this lifetime. The instincts are always there even if you don’t have literal memories.

Another thing that has happened with this September 8 is I have more pieces of my soul group than I did before. I don’t actively search for people in my soul group. I don’t feel like those things should be forced. Everything has a way of coming to you when it’s supposed to and when you can learn the most from it. Pushing things before you’re ready will only result in more confusion and unhappiness. I’ve never actively sought out people for my soul group or filling those missing slots even though I do have an intense curiosity about the concept. I do notice that we will find each other. It happens naturally. This past year I found one of my children from that lifetime – Grace, nicknamed Daisy. Just as with Wyllys and I switching generations with “him” being older than me now, so his Grace switched generations with me. Now I’m younger than both of them and they are older than me. That’s actually very common for parents and children to switch generations. Knowledge has been passed between myself and someone in my life now who was a close family friend back then too. He was someone I recognized the minute I met him about five or six years ago but we never talked about it until recently. I also have suspicions about one of my other children from our lifetime who died as an infant but, like I said, I don’t actively seek out members of my soul group. I wait for the answers to come to both of us naturally.

I suppose the moral of the story today is to consider what you might be doing in this lifetime that could be considered harmful to you. If you think you’re going to leave it behind when you die, you’re probably mistaken. Take the time now to resolve relationships that need work, resolve the relationship with yourself, and stop ignoring your problems. Be proactive and take control of your problems so that they don’t follow you in the future. Don’t make the same mistakes I did because you may be me in a couple of lifetimes from now looking back and wondering what the hell you’re having flashbacks and nightmares of a couple of centuries ago. It’s better to resolve things now instead of taking the baggage with you when you go.

And the most important thing to remember is that love is not going to end when people pass away. These relationships last much, much longer than most people think. It’s so important to nurture the important relationships in your life because at the end, you’re not thinking about how much money you made or how much fabulous stuff you acquired in your lifetime. You thinking about being around the people you loved. You’re thinking about what you would give to have one more hug or one more kiss or one more adventure.

Or one more birthday.

Adieu mio caro.

Read More