Credit goes to my friend, Gretchen, for posting this paragraph on Facebook today.

The roots of St. Valentine’s Day lie in the ancient Roman festival of Lupercalia, which was celebrated on February 15. On Lupercalia, a young man would draw the name of a young woman and then keep her as a “companion” for the year. Pope Gelasius I was less than thrilled with this custom. So he had both young men and women draw the names of saints whom they would then emulate for the year. Instead of Lupercus, the patron of the feast became Valentine. For Roman men, it became a tradition to give out handwritten messages of admiration that included Valentine’s name. Legend has it that Charles, duke of Orleans, sent the first real Valentine card to his wife in 1415, when he was imprisoned in the Tower of London.

I did some digging because Gretchen inspired me to dig. It seems that the origins lying in the festival of Lupercalia is a story from the nineteenth century that some modern scholars dispute. Scholars like to dispute everything! What is known for certain is that Valentine’s Day is documented back to the Middle Ages in the way that we know it today. In the mid-1600s, wealthy people exchanged elaborate gifts. Writing Valentine letters became very popular in the 1700s but special Valentine stationary was not marketed and sold until the 1820s. Valentine cards were introduced in the 1840s when postage rates became standardized in England. You know how Americans are – whatever England and Europe does, we copy and make our own. A woman in Worcester, Massachusetts, received a Valentine card from England and began selling some of her own design in her father’s stationary shop. So the American birthplace of Valentine’s Day was Massachusetts!

By Valentine’s Day in 1856, however, someone published an article in the New York Times denouncing the holiday. It read, in part:

Our beaux and belles are satisfied with a few miserable lines, neatly written upon fine paper, or else they purchase a printed Valentine with verses ready made, some of which are costly, and many of which are cheap and indecent. In any case, whether decent or indecent, they only please the silly and give the vicious an opportunity to develop their propensities, and place them, anonymously, before the comparatively virtuous. The custom with us has no useful feature, and the sooner it is abolished the better.

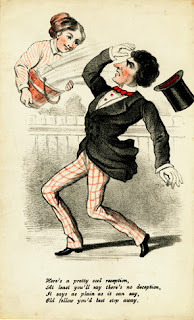

Nobody appears to have listened to the author of the editorial though because the holiday continued to grow in popularity after the Civil War. Victorians always had a knack for making everything beautiful, idealistic, innocent and sweet, and Valentine’s Day was like a ready-made holiday for them. In the years leading up to the Civil War and directly after, Valentine cards were enormously expensive and usually had little treasures hidden in them. The late-1860s saw the cards drop in price, lose the hidden treasures, and became easily accessible to the mass production American public. That was how it became the holiday we know today.

Here are some examples of Victorian Valentines.

Leave a Reply